The other boy working on the bus is black with short fuzzy hair that seems to grow out in small clumps. He’s shaped it so that it is longer in the central column like a flat Mohican. He leans against the glass that shields the passengers from the door and, left arm resting on his up-bent leg, watches the film.

It is unusual to see black people in Bolivia; the majority of the population come from golden-skinned indigenous stock, although it wasn’t until Evo Morales became President that an indigenous person held the highest office in the land.

When the Spanish discovered a gleaming mountain of silver at Potosí in 1544 it was the indigenous population, the Aymara and Quechua, who were sent down the hopeless tunnels for 12-hour stints of back-breaking labour amid the mercury vapours and darkness. Millions died, 90% of the indigenous population lost forever to the ‘Cerro Rico’, the ‘rich hill’ towering above the city that by the end of the century had the same population as London.

The Spanish rulers patched up their thinning workforce with African slaves. From the plains and jungles of Africa, from the Congo, Angola, Benguela and Biafra, they found themselves high in the Andes (the Cerro Rico rises to 15,827 feet) chewing coca leaves to numb themselves from the cold and the altitude, working for months at a time without seeing the sun. When they were finally taken out they’d be blindfolded to prevent their going blind. Some 30,000 Africans were shipped to Potosí, where they would typically last for no more than four months.

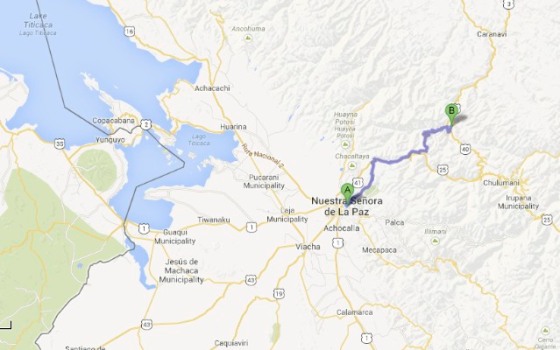

They escaped to the Yungas after emancipation. They streamed away from the forbidding heights down to where the mountains begin to melt away into the tropical lowlands. The next day we hike from Coroico down into the valley then up the other side to the Afro-Bolivian community of Tocaña.

It is in the Yungas where the coca leaves that kept the slaves working in the black corridors of Potosí are grown. During the week the men of Tocaña go out into the hills to find work in the coca fields. I wonder if they realise that just as their livelihood depends on the coca leaf, so their ancestors’ lives depended on it, for down in the mines those who could not fight the cold and the altitude and the hunger perished immediately. Only the coca-chewers had even a chance of survival.

Even after the exodus to the Yungas the afro-bolivians continued to be subjugated. It wasn’t until 1945 that ‘pongueaje’ y ‘mitanaje’ were abolished. The latter obliged the women, usually the daughters, of a family to work at the landowner’s house for free, whether it be the one in the country – the ‘hacienda’ – or the one in the city. They were not technically owned by the landowner (or ‘patrón’), but the fact that their labour was unpaid and unchosen made it tantamount to slavery, or one of those long unpaid internships that you’re required to do nowadays to get a job… ‘Pongueaje’ was a similar system, but only involving the male side of the family. They would have to do the gardening, or carry firewood, or build the shed at the end of the garden. All this would be done in addition to the – paid – labour in the fields.

In 1952, while the US were running around looking for Reds under the bed and London was drowning under a sea of smog and Gene Kelly was singing in the rain, Bolivia ended feudalism. For the first time Afro-bolivians could own land. Now there are 30,000, the same number that were brought to Potosí in the beginning. Most, like our bus boy, now live in the cities, in La Paz and Santa Cruz, while others maintain the life of the campesino in the afro-bolivian strongholds of Tocaña, Chijchipa, Santa Ana, Chicaloma or Chulumani.

To get to Tocaña we had to head down into the valley from Coroico, down through the slippery jungle, fighting off tiny malicious red midges and aggressive guard dogs, before crossing a bridge and heading up the other side. Before Tocaña there were two other communities, small clumps of bricks sprouting out from the hillside. We walked on and on for hours wondering where on earth this fabled village was, before stumbling upon it quite suddenly and finding no-one.

A motorbike passed us as we made our way down. On it were two black boys returning early from the fields. We looked at each other as if to say ‘yay, we saw someone from Tocaña!’. Then the guilt, for we were doing exactly as many Bolivians do: viewing afro-bolivians as rare oddities, as lucky charms instead of people.

This is part of the tragedy of the afro-bolivan story – that, at least in the Yungas, they live a marginalised life, a life hidden in the hills beneath the palm leaves and the murmuring clouds, dislocated from the rest of the world.

On our last day in Coroico, as I head up above our hostel to climb the hill on which Coroico sits, I meet a child of Tocaña who spends the week at school on this side of valley. He tells me that there are 42 families in the community, all afro-bolivian. They have precious little contact with the rest of the world. At school, sometimes. At the kiosk that caters for the builders directing the river. Buying and selling at the market. But nothing else. And so when other Bolivians look at them there is the same mix of fear and wonder as when they look at us, the pale gringos from a far-away land.

If you can read Spanish then this is informative: Pueblo Afroboliviano … cultura llena de tradiciones

King Don Julio. (Not the only Afro-Bolivian king.) (Photo: mundoweb)

November 2012